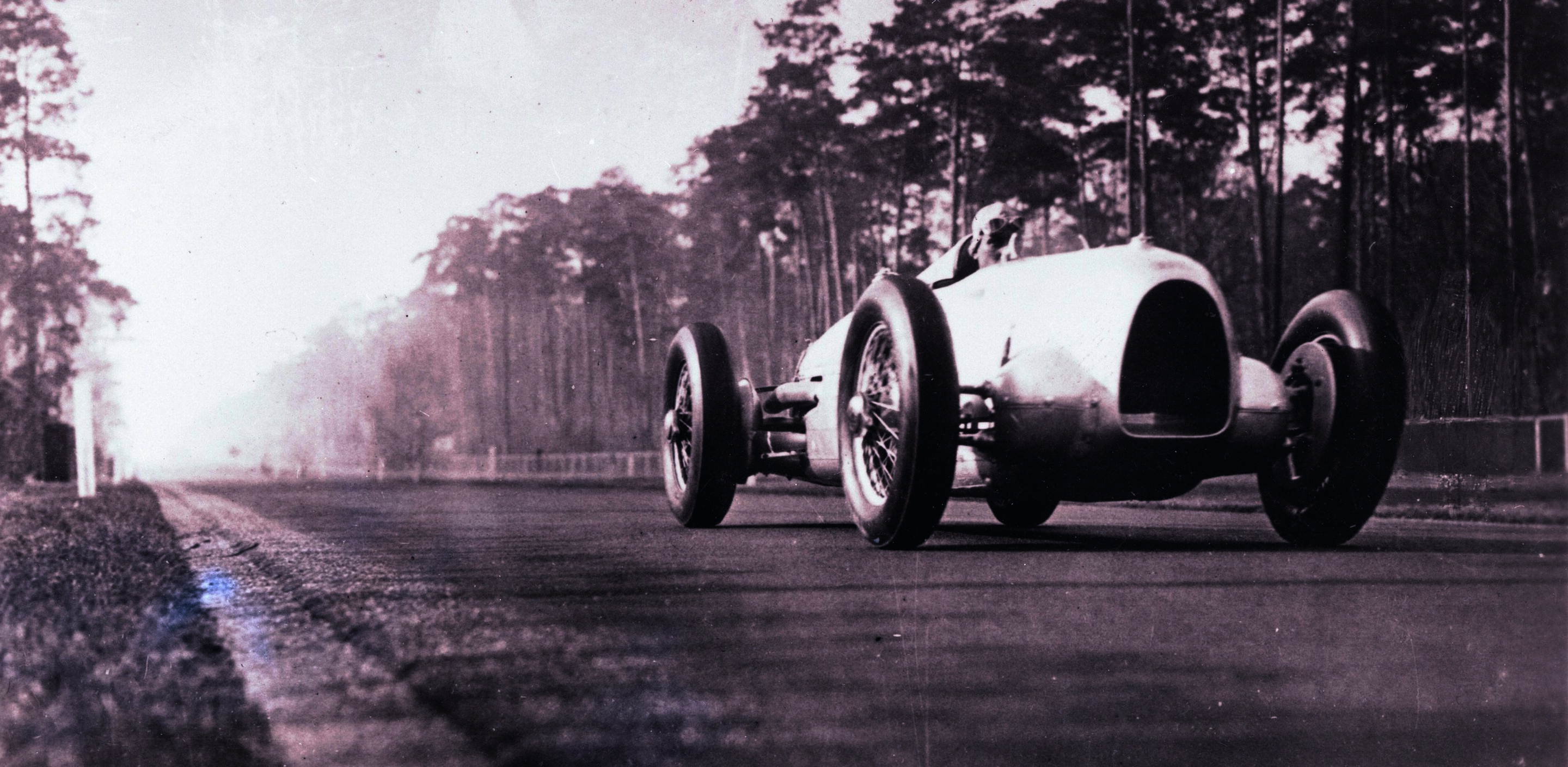

How the “Silver Arrow” legend was born

- 75 years ago, the Auto Union Silver Arrows went to the starting grid for the first time on the Avus circuit in Berlin

- Auto Union and Mercedes Benz dominated international motor racing between 1934 and 1939

75 years ago, one of the most dramatic chapters in the whole of motor sport history began. On May 27, 1934 the German racing cars that were soon to acquire the nickname “Silver Arrow” were entered for their first race, on the Avus racetrack in Berlin. Although neither Auto Union, the company from which Audi in its present-day form developed later, nor Mercedes Benz won that event, it was not long before these two manufacturers began to dominate international Grand Prix racing, a situation that prevailed until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. It seems almost incredible today, but by 1936 the Auto Union racing cars were reaching speeds of up to 380 kilometres an hour on the long straights of the Avus circuit – truly, the birth of a legend.

The racing cars bearing the four-ring emblem were entered for the race to be held on Berlin’s Avus circuit on May 27, 1934. Driven by Hans Stuck, August Momberger and Hermann Prince zu Leiningen, this was their first appearance in competition. They were given a striking silver paint finish, but possibly their most remarkable feature was that the engine was located behind the driver. 1934 was the first motor racing season in which the designers had to comply with a new formula: the cars were limited to a total dry weight of 750 kilograms, but the engines could be of any size and there was no restriction on the type of fuel.

Ferdinand Porsche was the brain behind the Auto Union racing cars, so to speak. He designed them for the new motor-vehicle manufacturing group of that name that had been created in 1932 by a merger of the Audi, DKW, Horch and Wanderer brands, and supervised their construction and testing from March 1933 onwards at Auto Union’s racing department, which was located at the Horch factory in Zwickau. Approval of his design was subject to the engines developing at least 250 horsepower at 4500 rpm. Driver Hans Stuck confirmed this with a world speed record run on the Avus circuit in March 1934.

During the Avus race held shortly afterwards, the new Auto Union racing cars put up a most impressive show. Even during practice, Hans Stuck’s average lap speed of 245 km/h had made it clear who was the fastest contender. Although the race itself was held in heavy rain, Auto Union outpaced the other entrants (with Momberger recording the highest average speed of 225.8 km/h). By the tenth lap, Stuck had built up a whole minute’s lead over his nearest rivals – but then a fault developed. At the finishing line, Momberger was third, behind Alfa Romeo drivers Guy Moll and Achille Varzi, so that a place on the podium was secure. And incidentally, the competing team with the three-pointed star as its badge was still struggling with obstinate technical problems and chose not to enter for this race at all.

The Auto Union Grand Prix cars went through three stages of improvement by the 1937 season:

1934 Type A: 295 bhp

1935 Type B: 375 bhp

1936/37 Type C: 520 bhp

During this period, the basic design concept remained unchanged. The V16 engine was in the centre of the chassis, behind the driver’s seat, and thus anticipated by several decades the layout used almost exclusively on modern racing cars. In its final form, the engine had a displacement of 6 litres and was extremely flexible: its maximum torque was 87 mkg at 2500 rpm, which meant that only a four-speed gearbox was necessary. A single camshaft operated all 32 valves; the crankshaft, originally a one-piece unit, was soon replaced by a version developed by Hirth, a specialist company. This consisted of individual segments bolted together through splined couplings.

The most famous drivers of these cars were Bernd Rosemeyer, Hans Stuck, Hermann Paul Müller, Ernst von Delius, Rudolf Hasse and Achille Varzi.

For the 1938 season, the formula changed and, since Ferdinand Porsche’s contract had terminated and he was no longer available, Chief Engineer Robert Eberan von Eberhorst drafted out a new design.

It’s possible to calculate very accurately just what participating in Grand Prix motor racing was costing the company. From the first to the final racing season, expenditure rose from 1.3 to 2.5 Reichsmarks (RM). In 1935, a complete racing car cost about 50,000 RM; four years later, the figure had risen to about 70,000 RM. A staff of approximately 60, including the race mechanics, was needed in the racing department, which was formed in 1933. Its members were specially chosen, in most cases from the workforce of the Horch factory in Zwickau, where the racing department was located.

Between 1934 and 1939, Auto Union spent about 13.2 RM on Grand Prix racing, and received approximately 2.7 RM in subsidies from the government, an annual average of about 20 percent of its costs. In those years, Auto Union entered for 61 circuit races in all, 30 of them Grand Prix events. It won 24 of the races for which it entered and also took 23 second and 17 third places. In 1934, 1936 and 1938 an Auto Union driver was German road racing champion.

By means of these motor sport successes, Auto Union was able to supply convincing evidence of its principal competence areas: aerodynamics, weight-saving construction and high-performance engines. At the same time, these specialised, highly tuned cars demonstrated the immense technical know-how, the precision machining methods and the skills possessed by Auto Union’s employees after many years of supplying products of consistent high quality.